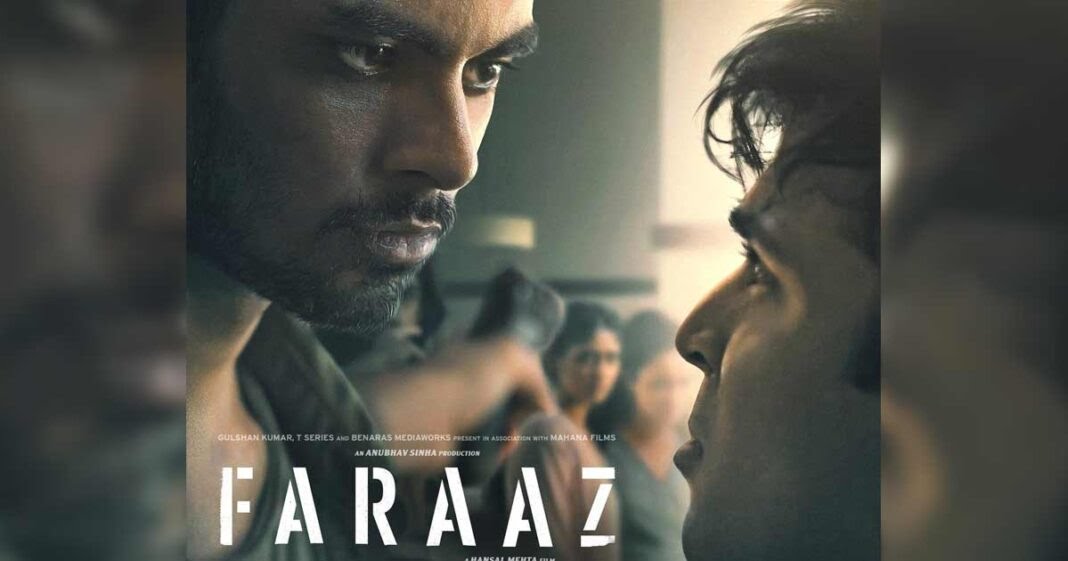

Hansal Mehta turns Bangladeshi mujahideen into ‘dudes’ from Bandra – Beyond Bollywood

The bizarre characters, tone, dramatization of the 2016 Holey Artisan Bakery terror attack was never going to appeal anyone in Bangladesh or India.

By Mayur Lookhar

Hansal Mehta is an acclaimed filmmaker from Hindi film industry. His films have never set the box office on fire, but Mehta has often earned praise for his maturity at handling sensitive subjects – Shahid [2013], Aligarh [2015], Omerta [2017] to name a few. Yours truly is an admirer of Mehta. He may divide opinions with his political views, but one has to give Mehta due respect for his film-making talent.

We’ve been blown away by some of his remarkable films/series. So, it comes as a shock that he made Faraaz [2023]. Barely marketed, Faraaz sank without a trace at the box office. We heard some praise from a few. That, however, is normal for Mehta. Classes, masses conversation is divisive. It is all about sensibility and Mehta’s works have always struck a chord with us.

We’re almost in disbelief that Faraaz [2023] is a Hansal Mehta directorial. He hasn’t written the film. That credit is shared by Ritesh Shah, Kashyap Kapoor, and Raghav Kakkar. Seven months later, it is too late to review a film. So, this is not a review but just dissecting few bizarre elements of the film.

In current times, a disclaimer is a vital information to every film/series. Seldom do filmmakers claim that their film mirrors the real. It is always based on,or inspired by true events. It often surprises as to how many filmmakers use the word ‘inspired by’ for tragic tales.

The Faraaz disclaimer is an intriguing one. It claims to be inspired by the attack that took place at the Holey Artisan Bakery on 1 July, 2016 in Dhaka, Bangladesh. In the very next sentence, it states that that are fictional elements in the film. It is neither documentary and does not claim to accurately reflect those incidents that may have occurred on that dark and horrific night.

Now you start of by being inspired by a true story, but you also add that this film doesn’t claim to be an accurate representation of what may have transpired. (What research then went in to make this film?) The Faraaz disclaimer also clarifies that certain characters. institutions, events have been dramatized.

This kind of disclaimer is least likely to help you form an opinion/perspective on the terror attack.

Desi viewers will question that here is a filmmaker who has made a film on Pakistani terrorist Omar Sheikh [Omerta], but never one on terror attacks in India, especially from across the border. Who are we to dictate a filmmaker? But it begs the question, what is there for Indian audiences/civilians in a film that is based on a terror attack in Bangladesh?

Near two hours later, we empathize with the cause, the larger message that Faraaz looked to address. We, however are bewildered by the character representation, tone and dramatization.

Maybe, the world has a general perception about terrorists. We presume them to be radicalized men sporting beards, wearing skull cap, pathanis. While radicalized women are known to wear hijab. 9/11 and other terror attacks around the globe have long dispelled the notion that such acts are merely the work of uneducated lot.

No one is questioning the education qualification of Mehta’s terrorists. One, however, is intrigued, astonished by the characterization/representation.

Five young radicalized Bangladeshi men – Nibras [Aditya Rawal], Rohan [Sachin Lalwani], Mubaseer [Jatin Sarin], Khairul [Nimaad Shaunak Bhatt], and Bikash [Harshal Pawar] are tasked to carry out a terror attack at Holey Artisan Bakery in Dhaka’s plush diplomatic area. They’ve planned to kill every non-Muslim that comes in their way. Nibras is leading this terror act. Their handler goes by the name of Rajiv [Godaan Kumar], quite possibly a cover-up name.

Save for Rohan, none of the other men sport long beards. They are all dressed in cool casuals. That helps to allay any suspicion about these men. Nibras, Rohan speak in English but the dialect, and the conduct of these men during their terror act, has bizarre written all over it. The English seeps in the moment Nibras spots Faraaz Hossain [Zahan Kapoor], his former batchmate with whom he played football. Faraaz is stuck with two of his friends, one of them is an Indian girl, whose identity will have to be protected if she is to survive.

The sizable English communication makes you question what is the primary language of this film? One is in disbelief when Nibras, Rohan mutter words like dude, chic, screw you in their conversation. Bangladeshis do speak English but presumably in their Bangla accent. The larger target audience is India, and so Mehta can be forgiven for the English words. The tone, the dialogues though compel you to think that rather than Bangladeshi mujahedeen, these terrorists strike you as ‘dudes’ from Bandra, Mumbai [India].

Faraaz and his friends are a privileged lot. They have studied from foreign universities. Faraaz’s family has political connections too. We’re aren’t sure about Hindi audiences, but did their English tones appeal to Bangladeshi audiences?

Coming back to our terrorists, you question the level of their radicalization? Usually, such terrorists deem materialism, entertainment as haram [forbidden]. But clearly, the football fan in Rohan and also Nibras isn’t dead yet. One also has to question the competence of these terrorists?

Jeez, in a hostage crisis, any terrorist would first disarm his victims, confiscate their gadgets. Most of the hostages here carry their cell phones. After dealing a blow to the Bangladesh local police, the men just relax. The Bangladeshi RAB [Rapid Action Battalion] are made to wait, told directly by their PM to negotiate with the terrorists till the army arrives. But we don’t really see any negotiations save that RAB wouldn’t harm the terrorists if they released all hostages. Nibras, though, has come with jannat [heavenly] aspirations. You are taken aback when Rohan refuses this heavenly idea.

Faraaz’s attempts to make Nibras change his mind in a hostage crisis is bizarre. For a man who was pretty clear in his head to not kill even one Muslim, Nibras stuns you when he doesn’t harm a local Hindu chef. This after the latter had lied about his identity to the terrorists. The chef convinced the terrorists that his name is Sardar Khan, and not Sarkar, as printed on his chef coat. He puts that down to a printing error. Moments later, two terrorists accompany Sardar in the kitchen. As he cooks for all. Rohan seizes his phone, finds the wallpaper of Maa Durga [Hindu goddess], yet the terrorists let the man live. Jeez, we’ve never seen such lenient Islamic terrorists before. Not a single of these so-called terrorists convince you.

All throughout the film, Mehta’s terrorists are cold in their gruesome killings. The despicable men derive voyeuristic pleasure by pumping in bullets on the dead (foreigners) too. All this to make it look like a deadly terror act. Normally, in a terror plot, it is reasonably fine to show certain barbaric nature. There, however, has to be karma in the climax, where viewers, victims, or their families get a sense of justice seeing these evil men being battered black and blue. Stunningly, we don’t see any karmic justice. The Bangladeshi army pile on the bullets into every corner as they march inside the plush property. We don’t see the terrorists dying. Often such tropes are reserved for protagonists who die as martyrs. How could Mehta or his writers miss the essence of karmic justice?

The terrorists are a joke but Zahan’s mother Simeen [Juhi Babbar] leaves you scratching your head. The Hossains are a privileged family, with strong political connections. Simeen isn’t afraid to flaunt it. She uses it to intimidate police officials at the terror scene. While this could be justified as a desperate act to save her son and his friends, but as a viewer, it doesn’t build any empathy for these characters.

In the context of this story, Zahan Kapoor and Juhi Babbar’s casting makes for an interesting reading. The former is the fourth gen actor from Bollywood’s famous Kapoor family. Zahan made his debut with Faraaz. Juhi is the daughter of veteran actor Raj Babbar. She’s been around for a while, but has largely struggled for consistency and plum opportunities. Was it wise for two ‘insiders’ to take up roles that will show them as privileged?

At 44, Babbar may not have much to lose. You do question though Zahan’s choice of Faraaz as his first film. It can be viewed in two ways. Now, either he’s erred by playing a privileged lot. Alternatively, one can say that privileges don’t count for anything in matters of life and death. Keep the Dhaka terror plot aside, we live in an age where nepotism is abhorred by ordinary fans, who aren’t afraid to pile the pressure on a nepokid. So, Zahan opting for a Faraaz as his first film was indeed a gamble that has misfired.

The reaction that came from Bangladesh wasn’t flattering. Mehta was accused of exploiting the tragedy for personal gains, and not bothering to take the consent of the victims or their families. Mind you, such real tragedies can’t really fall under any Copyright claim unless, it is a biopic. But with the title and the story being largely told from Faraaz’s predicament, should Mehta have taken consent from the family? We don’t know but maybe, he took one from the Hossain family.

Ruba Ahmed, a victim’s mother, had filed a writ petition accusing the film of misrepresentation and sought a ban on the film. The Bangladesh High Court obliged and banned its theatrical and online release.

For close to two hours, we couldn’t decipher as to who or whom is this film made for? With the way it panned out, it surely is not one backed by any Bangladeshi subsidy. The characters, the tone, treatment doesn’t quite cater to the desi palate either. Did Hansal Mehta, producers Anubhav Sinha, T-series merely eyed the ‘festival’ audience? That it hasn’t won any noted international acclaim makes you question their motto? Maybe, one day we will get some answers from Hansal Mehta.

Bangladesh banned it. Faraaz bombed in India. OTT networks aren’t obligated to reveal the true viewership. Given the largely negative response, we can say with certainty that this film wouldn’t have appealed to Bandra folks too. Sadly, Faraaz fizzles out as a poor representation of a terror act. More disappointingly, it does nothing for Faraaz Hossain and other victims of the Holey Artisan Bakery terror act.

Publisher: Source link

5 Bollywood Films To Watch To Brighten Your Day

Sightless, yet soulful – Beyond Bollywood

Aankhon Ki Gustaakhiyan Movie Review

Maalik Movie Review – Bollymoviereviewz