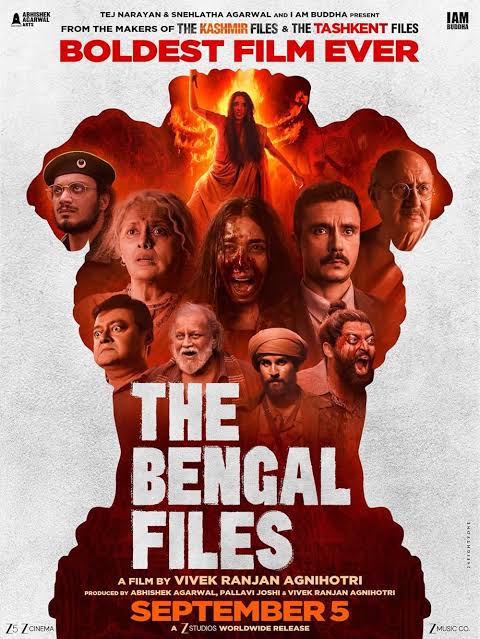

Dedicated to the victims of communal violence, really? – Beyond Bollywood

Brief as it is, Vivek Ranjan Agnihotri finally condemns violence on all sides. Compelling in its narrative, it’s driven by intense acts from Darshan Kumaar, Saswata Chatterjee, and Mithun Chakraborty, with Nimrat Kaur, Eklavya, and Namashi Chakraborty also leaving their mark.

Rating: ⭐️⭐️⭐️ (3 / 5)

By Mayur Lookhar

There’s no point sulking over a body part amputated long ago. That missing part was split further in 1971 – you played a role, but it was never coming back.

Fast forward to the 21st century: Noakhali, a town in Bangladesh (formerly East Pakistan), is a place most young Indians haven’t heard of and probably care little about. Here comes an Indian film that takes us back to a time (1946) when communal riots broke out there.

Given India’s longstanding Non-Alignment Policy and commitment to strategic autonomy, it isn’t customary to comment on domestic issues in neighbouring countries. Yet the political upheaval in Bangladesh, and the spate of hate crimes against Hindus last year, was rightly condemned across India. #SaveBangladeshiHindus became a rallying cry in Indian media and social media alike. Before becoming US President for the second time, even Donald Trump had expressed concern over the situation. Trump, however, has turned the screws on India today with his tariffs.

Last winter might have been an appropriate time to release The Bengal Files (2025), and it wouldn’t have been too close to the upcoming 2026 West Bengal Assembly elections – still 8–9 months away. Fearing unrest, many exhibitors in the state have chosen to play it safe and refused to release the film. One can hardly blame them.

Domestic politics aside, the sentiment sparked by the 2024 turmoil in Bangladesh is bound to generate curiosity for writer-director Vivek Agnihotri’s The Bengal Files.

Story

This story revolves around two files – one largely forgotten from 1946, and another in the present day, about the disappearance of Geeta Mandal, a young Dalit journalist from Murshidabad, West Bengal.

Whether it’s Noakhali in 1946–48 or Murshidabad today, Bharati Banerjee was there during the dark times. If she was around 20 back then, she’d be 99 now. Frail and forgetful, she is nonetheless the only hope for CBI officer Shiv Pandit (Darshan Kumaar) to find Geeta Mandal. The prime suspect is Sardar Husseini (Saswata Chatterjee), a powerful local MLA.

Screenplay & Direction

With The Bengal Files, Vivek Agnihotri completes a trilogy, though it seems unlikely he’ll stop uncovering more files in the future. The Tashkent Files (2019) was purely political, while The Kashmir Files (2022), though it struck a chord with displaced Kashmiri Pandits, didn’t cover that dark chapter in its entirety. Perhaps to avoid similar criticism, Agnihotri, for the first time, offers a relatively balanced perspective, at least in the way he approaches the Noakhali files from 1946–1947.

Huseyn Shaheed Suhrawardy (Mohan Kapoor), then Prime Minister of Bengal and later Prime Minister of Pakistan, is shown brutally exposed for inciting communal hatred that led to the Direct-Action Day Riots in Noakhali. The Muslim League and its violent call for Pakistan is spelt out loud, but Agnihotri does not shy away from briefly depicting retaliatory violence from the other side, justified, at least in the eyes of the perpetrator Gopal Patha (Sourav Das), as an act of self-defense. Patha’s grandson had slammed Agnihotri and the film for its false portrayal.

The opening disclaimer puts the casualty figure of the Noakhali riots to about two million. A 2014 article in TIME.com, put the estimated death toll to anything between 5000 to 20,000.

Genocide or not, death of a single innocent civilian ought to be condemned. Agnihotri’s film condemns all violence in the name of religion, exposing those who use religion to incite mob violence. The Bengal Files is essentially a cry against this mob mentality.

There’s likely to be broad agreement on the points above, but the film also subtly raises questions about the ruling party in West Bengal and the culture of goondaism that has long been part of regional politics. The Geeta Mandal case subtly hints at the 2024 Sandeshkhali case, where serious allegations of sexual assault and land grabbing were made against former TMC leader Sheikh Shahjahan. The case has since become a flashpoint between the ruling TMC and their main opponents, the Bharatiya Janata Party.

We leave the politics to the politicians, but with Assembly Elections in Bengal next year, left-leaning critics might question the decision to include the Geeta Mandal story in The Bengal Files. In our view, the film handles the pre-Independence conflicts fairly objectively, portraying the Muslim League as the primary antagonist. The contemporary fictional crisis in Murshidabad, however, is bound to provoke differing opinions.

A runtime of 204 minutes naturally sparks fears of a drag, but the film’s strong writing and direction keep viewers largely engaged. Most agenda-driven films rarely fall into capable hands. Agnihotri has had his critics, yet to be fair, he remains the only filmmaker who owns these subjects and isn’t afraid to engage in objective debates. Unlike The Tashkent Files and The Kashmir Files, he avoids relying on too many closed-door conversations. Here, it’s the action and drama that does that most of the talking.

Acting

Agnihotri’s films rarely attract mainstream actors, many of whom likely see them as too risky. The filmmaker often relies on a mix of seasoned veterans, actors who’ve faded from the spotlight, and a few ambitious young talents.

The Kashmir Files perhaps proved too much of an ask for Darshan Kumaar. Him leading The Bengal Files was fraught with risk, but Kumaar doesn’t disappoint his director. The Kashmir connection is worth noting: in The Kashmir Files (2022), Shiva Pandit and his mother Sharda are brutally killed. In The Bengal Files, Shiv Pandit (Darshan Kumaar) also lost loved ones to terrorism in Jhelum, but he is an entirely different character.

The dynamic officer arrives in Murshidabad full of optimism but is soon disheartened by the harsh realities of the region. His boss, and uncle, Rajesh Singh (Puneet Issar) repeatedly reminds him that it’s best to remain neutral here, a subtle nod to the millions who generally avoid controversy unless personally affected. For much of the film, Pandit appears overwhelmed, yet Darshan Kumaar brilliantly captures his inner turmoil. Kumaar surprises with what may well be the defining role of his career.

Through Pandit, Agnihotri sparks intriguing exchanges with key characters, even giving Sardar Husseini room to bust myths about himself in his personal space. It also serves as a stark reminder of how figures like Husseini exploit religion for vested interests. The Kashmir Files had drawn criticism for leaning toward an “us versus them” narrative, but this time Agnihotri seems more mindful, allowing space for objective voices from the minority community. While Gandhi (Anupam Kher) is portrayed as meek, it is a Kashmiri Muslim who reminds Jinnah (Rajesh Kher) that the majority of Muslims rejected his two-nation theory and chose to remain in India.

Sardar Husseini may be the villain of the present, but the butcher of the past is his grandfather, the menacing Gholam Sarwar Husseini (Namashi Chakraborty), shown as the leader of the Miyar Fauj during the Noakhali riots of 16 August 1946. His descendants and followers may continue to deny the allegations of rioting and forced conversions, but after The Bengal Files, the Husseini name is likely to be remembered with lasting hostility in India.

Written off after his debut film, Namashi redeems himself as the surprise package here, evoking fear first in uniform and later in his Maulvi avatar. There was nothing particularly bad about him in Bad Boy (2023), but it’s in The Bengal Files that Namashi truly commands fear.

It’s a Chakraborty show here, with father Mithun impressing as Madman Chatur, one of the victims left to rot on the streets of Noakhali. Amid the rioting, Chatur gathers the sacred threads of the dead, a haunting reminder that while religion is easy to identify, what we often forget is that those killed in senseless violence were Indians first. Noble thoughts on screen, though one wishes the legendary actor-politician was as measured in his political speeches, unlike the retaliatory hate speech he delivered in the presence of the Union Home Minister in 2024.

Mithun da’s daughter-in-law, Madalsa Sharma (wife of his elder son Mimoh), stands out as Mrs. Sardar Husseini, a portrayal far from what one might expect. Altogether, the Chakrabortys do a fine job on screen.

Anupam Kher cuts a sorry figure as Gandhi, reducing the ‘Father of the Nation’ to a meek presence. Gandhi’s controversial remarks on women choosing death over dishonour are factually accurate, but it’s important not to lose sight of the context. For centuries, similar practices existed in the form of Jauhar, and Gandhi’s suggestion, likely made in an emotional moment during the latter stages of his life, shouldn’t be read in isolation. Though not really antagonising, the portrayal of a young Mujibur Rehman as a student leader is not flattering either, which should not please his loyalists in both Dhaka and Delhi.

Pallavi Joshi had made the shift from the resident urban Naxal to a saviour in The Vaccine War (2024). With The Bengal Files, she embodies the pain of a victim of hate crime. The seasoned actor, however, doesn’t entirely convince as the octogenarian Bharati Banerjee.

The real revelation is Simratt Kaur as the younger Bharati. The young Sikh actress, who appeared listless in Gadar 2 (2023) and Vanvaas (2024), takes the plunge into political cinema and truly owns her character. Bengalis are best placed to judge, but to us, she seemed fairly competent in her few Bengali lines. It’s nothing short of a miracle how her character survives the riots of 1946–1948, yet Kaur maintains a powerful presence throughout. The role is loosely inspired by Bina Das, the Bengali revolutionary who, in 1932, attempted to assassinate Sir Stanley Jackson, the Governor of Bengal.

Vivek Agnihotri throws in a Sikh character to the Noakhali mix, with debutant Eklavya Sood impressing as Amarjeet Arora, the man who saved Simratt’s Bharati on a few occasions.

Music / Technical aspects

Agnihotri preferred a raw approach in The Kashmir Files. The Bengal Files, too, is an intense story, but this time he allows space for a limited yet effective background score that complements the grim mood. Attar Singh Saini’s cinematography, especially in the violent sequences, and the production design by the late Rajat Poddar, along with his associate Pradeep Banerjee, truly stand out.

Final Word

Agnihotri’s socio-political films have always polarized views, and The Bengal Files is no exception. In the days ahead, it is bound to spark debate in social political circles , particularly because it revisits a relatively lesser-known chapter of Indian history. But will it fuel an even stronger sense of Hindu nationalism? Perhaps that’s the fear. Yet in today’s global and regional geopolitics, nationalism itself feels caught in limbo. Is wearing it on our sleeves truly worth it, when the very ecosystem that drives this narrative often bends to vested interests?

Agnihotri dedicates such films to victims of communal violence. So, watch The Bengal Files, but without anger, without ill will. Be it 46, 47, 84, 89, 90, 92, or 2002, khela chalta rahega, but don’t fall prey to mob mentality. Remember, mob mentality has only ever led to chaos and bloodshed. India has already lost enough blood through the ages.

Watch the video review below.

Publisher: Source link